Sweeteners

Your body is not "fooled" by sweetness with 0 calories!

A 2014 study (Nature, 2014) revealed a direct cause and effect relationship between consuming Non-nutritive Artificial Sweeteners (NAS) and developing elevated levels of HbA1C ( a long-term measure of blood sugar) compared to non-users or occasional users of NAS. This eye-opening study with both mice and humans found that NAS directly modulate the microbiota to induce glucose intolerance (i.e. prediabetes).

Artificial non-nutritive sweeteners (NAS) are toxic to gut bacteria, increasing risk of prediabetes

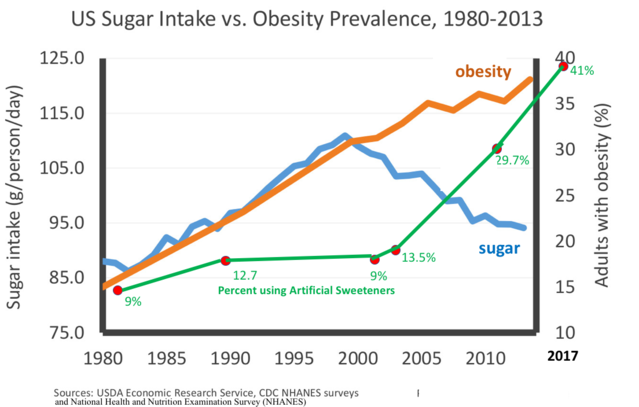

Percentage of U.S. population using artificial sweeteners rising with adult obesity rate

whilst sugar intake per capita on the decline since the late 90's

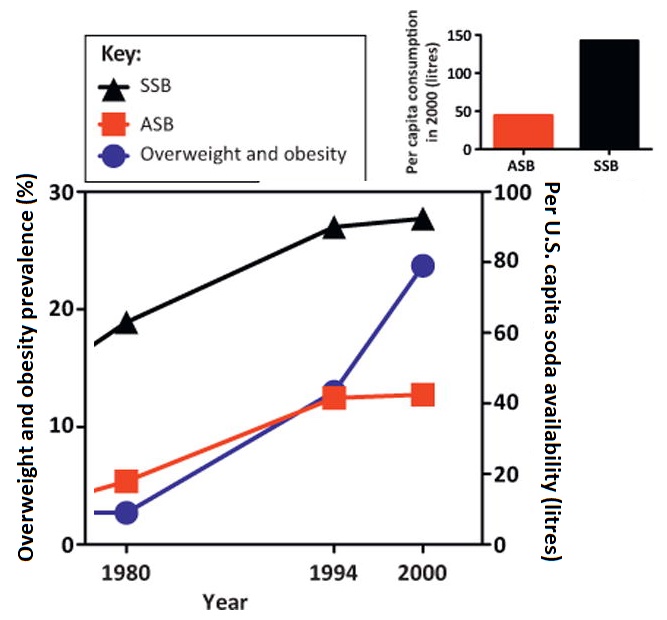

ASB and SSB beverage consumption associated with percentage of obesity / being overweight in U.S. population

Graph indicates changes in per capita consumption of artificially sweetened beverages (ASB; red squares), sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB; black triangles), and the rise in percentage of population being overweight. Obesity data adapted from National Center for Health Statistics Health. Beverage data adapted from Beverages Worksheet. USDA Economic Research Service.

Although rate of increase in both artificial and sugar sweetened beverage consumption has much declined since the mid-90's, obesity rates continue to rise sharply, indicating additional factors are involved.

Many people find it easier to lose weight by cutting out nutritive sugars instead of replacing them with artificial sweeteners

Several large scale prospective cohort studies found a positive correlation between artificial sweetener use and weight gain (Qing Yang, 2010)

- The San Antonio Heart Study:

• 3,682 adults over 7-8 yrs during 1980's had consistently higher BMIs at the follow-up. Average BMI gain was +1.01 kg/m2 for control and 1.78 kg/m2 for people in the third quartile for artificially sweetened beverage consumption.

• Participants who drank more than 21 diet drinks per week were almost twice as likely to become overweight or obese as people who didn't drink diet soda.(Fowler et al, 2008)

- The American Cancer Society study

• 78,694 women in early 80's

• At one-year follow-up, 2.7 - 7.1 % more regular artificial sweetener users gained weight (although <2#) compared to non-users matched by initial weight. (Stellman & Garfinkel, 1986)

- Another American Cancer Society study

• Saccharin use was also associated with eight-year weight gain in 31,940 women from the Nurses' Health Study conducted in the 1970s

- Increased diet soda consumption in children associated with increased weight gain (Colditz et al, 1990)

• 166 school children over 2 years

• Higher BMI Z-scores (indicating weight gain) found at follow-up (Blum et al, 2005)

- "Growing Up Today" study (Berkey et al, 2004) reported diet soda consumption by boys (but not girls) associated with weight gain:

• 11,654 children aged 9 to 14

• Each daily serving of diet beverage increased BMI by 0.16 kg/m2

- A cross-sectional study of young people (Forshee & Storey, 2003) found diet soda drinkers had significantly elevated BMI

• 3,111 children and youth

- Interventional studies suggests that artificial sweeteners do not help reduce weight when used alone(Mattes & Popkin, 2009; Brown et al, 2006)

• BMI did not decrease after 25 weeks of substituting diet beverages for sugar-sweetened beverages in 103 adolescents in a randomized controlled trial, except among the heaviest participants(Ebbeling et al, 2006)

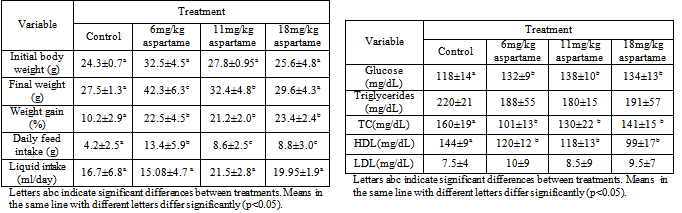

One study fed rats yogurt sweetened with saccharin, aspartame or sucrose for 12 weeks + normal rat food. Rats fed zero calorie artifical sweeteners had increased weight gain compared to sucrose (table sugar) fed rats. The no-cal sweeteners caused them to increase their appetites for normal food (Fernanda et al, 2012)

Rat feeding study found that breaking the link between the sweet taste of saccharin and the anticipated high calorie food changed the body's ability to control food intake.

• Rats were fed either saccharin or glucose sweetened yogurt. The rats that ate the saccharin-sweetened yogurt consumed more calories, put on more weight, gained more body fat, and did not cut back on their calorie consumption in the longer term (Swithers & Davidson, 2008)

At the end of a 24 week study, rats consuming sucralose gained weight compared to the ones that didn't. (Qing, 2010)

Substitution of artificial sweeteners for sugars in drink prevents weight gain and promotes weight loss in rats eating food without restriction. This 16 week study seemingly supports the use of artifical sweeteners for weight loss. However, here are the details:

81 rats eating food at will gained the same weight as controls when also drinking saccharin solution, but gained significant weight when drinking 11% sucrose solution instead of saccharin solution. When the sweetened solutions were switched, obese sucrose-drinking rats lost weight during the next 8 weeks while rats previously on saccharin gained weight rapidly. It is fairly obvious that weight gain (weight loss) would occur if adding (or removing) extra sucrose calories. (Porikos & Koopmans, 1988)

Berkey CS, Rockett HRH, Field AE, Gillman MW, Colditz GA. Sugar-added beverages and adolescent weight change. Obes Res. 2004;12:778-788. PubMed

Blum JW, Jacobsen DJ, Donnelly JE. (2005) Beverage consumption patterns in elementary school aged children across a two-year period. J Am Coll Nutr. 24:93-98. PubMed

Brown RJ, de Banate MA, Rother KI. (2010) Artificial Sweeteners: A systematic review of metabolic effects in youth. [Epub 18 Jan 2010];Int J Pediatr Obes.

Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, London SJ, Segal MR, (1990) Speizer FE. Patterns of weight change and their relation to diet in a cohort of healthy women. Am J Clin Nutr. 51:1100-1105. PubMed

Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Osganian SK, Chomitz VR, Ellenbogen SJ, Ludwig DS. (2006) Effects of decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on body weight in adolescents: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Pediatrics.117:673-680. PubMed

Fernanda de Matos Feijó et al, (January 1, 2012) Saccharin and aspartame, compared with sucrose, induce greater weight gain in adult Wistar rats, at similar total caloric intake levels Appetite, Volume 60, Pages 203-207 Abstract

Forshee RA, Storey ML. (2003) Total beverage consumption and beverage choices among children and adolescents. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 54:297-307.PubMed

Fowler SP, Williams K, Resendez RG, Hunt KJ, Hazuda HP, Stern MP. (2008) Fueling the obesity epidemic? Artificially sweetened beverage use and long-term weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 16:1894-1900. . PubMed

Mattes RD. (1994) Interaction between the energy content and sensory properties of foods. Birch G, Campbell-Platt G, editors. , eds Synergy. Hampshire, United Kingdom: Intercept, Ltd, 39-51.

Mattes RD, Popkin BM. (2009) Nonnutritive sweetener consumption in humans: effects on appetite and food intake and their putative mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 89:1-14. PMC free article PubMed

Nature (Oct. 2014) 514: 181-186 Article

Porikos KP, Koopmans HS. (1988) The effect of non-nutritive sweeteners on body weight in rats.Appetite.11 Suppl 1:12-5. PubMed

Stellman SD, Garfinkel L. (1986) Artificial sweetener use and one-year weight change among women. Prev Med. 15:195-202. PubMed

Swithers SE, Davidson TL. (2008) A role for sweet taste: calorie predictive relations in energy regulation by rats. Behav Neurosci. 122:161-173. PubMed

Qing Yang. (2010 June) Gain weight by "going diet?"Artificial sweeteners and the neurobiology of sugar cravings. Neuroscience 2010.Yale J Biol Med. 83(2): 101-108. PubMed